A former senior official of the Iranian regime has disclosed that despite numerous promises made in the past decades to restore Iran’s environment, the country currently lacks ‘a single flowing river, living wetland, or watery lake.’

Issa Kalantari, the former head of the Environmental Protection Organization, told the website ‘Khabar Online’: ‘The significant crime’ occurring is ‘underground,’ and almost no one is paying attention to it, including officials from the Ministry of Energy, the government, and the general public.

He added: ‘Currently, there is a rush to draw underground water to the surface and evaporate it, seemingly to support agricultural development.’

Several Iranian newspapers, on World Wetlands Day (February 2), highlighted issues of drought, reservoir loss, and neglect by the Environmental Organization and other entities.

The loss of wetlands leads to consequences such as land subsidence, aquifer drainage, climate changes, and the increase of fine dust.

On February 3, Shargh newspaper, in a report titled ‘Domino of Destructive Works,’ interviewed Mohammad Masoud Tajrishi, head of the climate change and environment think tank of the Academy of Sciences, about Lake Urmia’s situation. Tajrishi emphasized that even basic statistics of Lake Urmia, such as its level, have not been published in recent years.

Satellite images reveal a continuous decrease in the area of Lake Urmia, from 3,144 square kilometers in February 2018 to 192 square kilometers this year.

The restoration of Lake Urmia requires at least 3,426 million cubic meters of water, with only 40% of this needed water supplied from natural rainwater and seasonal rains.

Almost all of Iran’s permanent wetlands have transformed into seasonal wetlands. Some, like Parishan, Bakhtegan, Gavkhouni, and Kaftar, have lost the possibility of seasonal water intake in certain years. In the north of Iran, wetlands have suffered, and the Caspian lake has receded.

In mid-January, pictures of the beginning of the mulching project on the shores of Lake Urmia in Ajabshir were published, causing concern.

Simultaneously, Payam-e Ma newspaper reported that the lake needs 3.4 billion cubic meters of water for restoration, whereas officials have promised only 2 billion cubic meters. This discrepancy has led to considering mulching in some areas and water supply in others to prevent the rise of dust storms.

In recent years, reports and warnings about the consequences of Lake Urmia drying up, the creation of storm platforms, and the occurrence of micro dust in the region have been published. Due to the lake’s salty bed, concerns are multiplying.

Iran faces a complex, multi-dimensional problem with severe environmental, economic, and social effects, extending beyond the lake’s surrounding areas to several provinces.

Currently, all wetlands in Iran are vulnerable, despite appearing physically healthy. Sustainability conditions are exceedingly weak, with the water rights of wetlands remaining unallocated.

In the past decade, except for the rainy years of 2018 and 2019, most wetlands have faced water rights problems and drought.

Iran’s Wetlands Protection Plan commenced 18 years ago in collaboration between Iran’s Environmental Protection Organization, the Global Environmental Facility (GEF), and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). However, there is no information about its fate or termination after two decades.

Although ecological programs for over 40 wetlands have been prepared, they remain unimplemented. Protests against Lake Urmia and other wetlands drying up are met with authorities dismissing them as ‘normal’ and hoping for ‘fall rainfall’ for their revival.

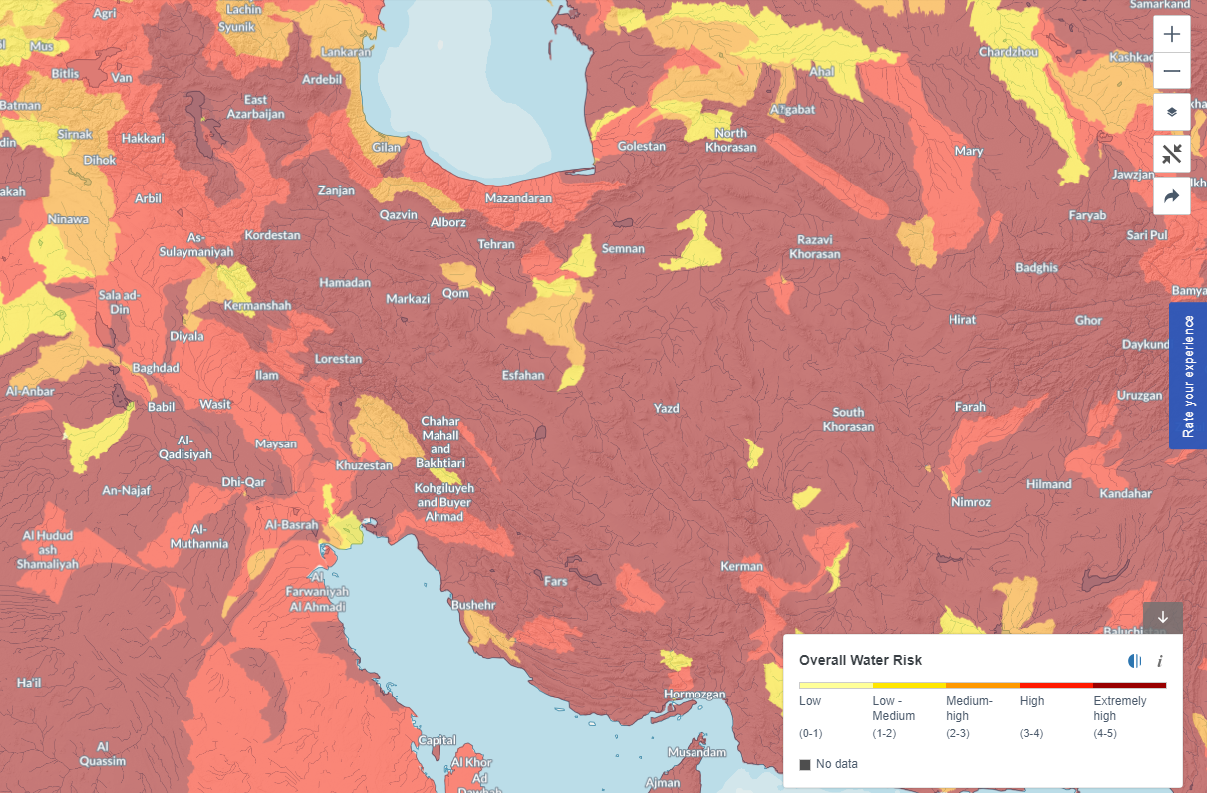

According to the water risk atlas provided by the World Resource Institute, Iran ranks among the worst countries in terms of freshwater availability. The underground water level has drastically dropped, and with the drying up of main lakes and rivers, the country is approaching a state of complete drought.