“Every deal, every negotiation with the regime, it means additional gallows in Iran,” says Shabnam Madadzadeh, 29, the famous student organizer at Tehran’s Tarbiat Moalem University who spent five years in confinement in Iran’s notorious Evin prison.

Ms. Madadzadeh escaped her home country via a clandestine network operated by the People’s Mujahedeen of Iran, or MEK, just a few weeks ago. Now staying in Paris, she appeared Saturday at a conference with other Iranians who are opposed to the hard-line officials who run the country.

“Iranian people do not want negotiations with this regime, and they hate appeasement policy with this regime,” Ms. Madadzadeh told The Washington Times. “They want the world, European governments and United Nations and the U.S. to stay firmly against the regime’s policy of violence against human rights — the regime’s crimes in Iran and Syria and exporting terrorism in the world. Iranian people want a change in regime by themselves and resistance.”

A 2010 State Department report on human rights violations in Iran singled out a prosecutor who consistently imprisons dissidents. Ms. Madadzadeh is one of his victims. The report said, “Tehran public prosecutor, Saeed Mortazavi, the most notorious persecutor of political dissidents and critics. According to international press reports, Mortazavi was put in charge of interrogations at Evin prison, where most of the [2009] post-election protesters were detained.” The report goes on to say, “On February 19, authorities arrested Shabnam Madadzadeh, a member of the Islamic Association and deputy general secretary of the student organization Tahkim Vahdat, along with her brother Farzad Madadzadeh. Authorities accused her of disseminating propaganda against the state and ‘enmity with God.’ Despite her lawyer’s protests against her detention, the judge refused to assign a bond for her release, arguing that she was a flight risk. As of mid-October, she was reportedly being held in the women’s general section of Evin prison.”

As reported by the State Department a year later, Ms. Madadzadeh was sentenced to five years in prison for spreading anti-state propaganda. She had no lawyer present , as authorities had detained him for protesting the death sentence of a teenager on a charge of murder.

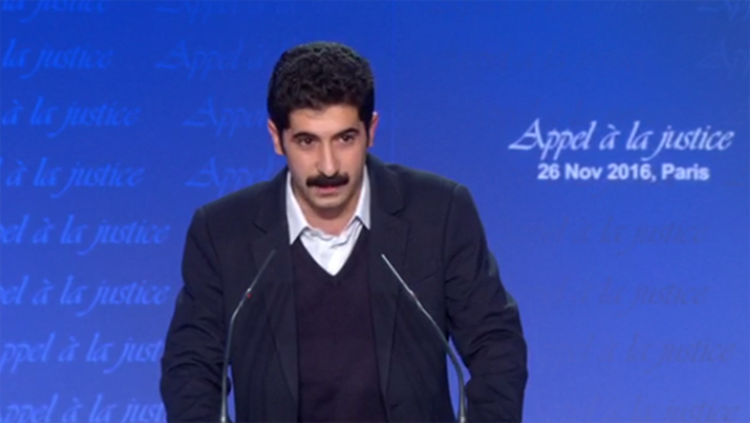

Arash Mohammadi, 25, is another recent escapee. He took part in street demonstrations in Tehran over the reelection President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2009, amid charges of ballot fraud.

“I was on the streets,” Mr. Mohammadi said in his native Farsi, through an MEK interpreter. “The chants, ‘Obama, Obama, are you with them or with us?’” Mr. Mohammadi, a college student, was arrested three times for publicly protesting against the regime. He was imprisoned for two years. He states that intelligence interrogators beat and threatened him, and even offered him money to denounce the MEK and become an accepted reformist. He says he refused and now plans to be “a voice for the voiceless.”

His message to President-elect Donald Trump is this, “The responsibility for change is with me and my generation. We are the force for change. If the West wants to have a good reputation in Iran, my point is, side with us. Side with the resistance. History will remember you in a good way. That’s for your betterment and for Iranian people’s betterment.”

Both Ms. Madadzadeh, Mr. Mohammadi are seeking asylum in Europe. It is the two dissidents’ contention that human rights abuses are getting worse since the April 2015 nuclear deal.

This appears to be supported by the U.N. In October, U.N. General Secretary Ban Ki-Moon issued a report condemning Iran’s treatment of its people. “Human rights violations have continued at an alarming rate,” Mr. Ban said. “In particular, a significant number of executions took place, including of individuals who were juveniles at the time of the alleged offense; corporal punishment, including flogging, persisted; the treatment of journalists and human rights defenders remained of concern, as raised by several United Nations human rights mechanisms; and religious and ethnic minorities continued to face persecution and prosecution.” He added, “At least 966 people were reportedly executed in 2015, the highest such number in over two decades, in continuation of an upward trend that began in 2008. During the first half of 2016, at least 200 people were executed. Executions are often carried out following trials that fall short of the international fair trial standards guaranteed.”

According to Tehran, most prisoners are executed for drug trafficking.

The new money flowing in from the West is not going to alleviate poverty, create jobs or stop rampant child labor, says Ms. Madadzadeh, but is being funneled to the Revolutionary Guard Corps and its overseas operations. “Nothing changed in Iran’s people’s life” she said. “The deal was just with the regime. The guards of the regime, the one that was spending money to export terrorism and was spent in Syria and [for] the suppression of the Iranian people. Not for the freedom. Not for people.”

Ms. Madadzadeh spent five years in various prisons, including Evin’s Section 209 run by the Ministry of Intelligence. She says she was beaten, threatened with rape and subjected to fake executions. “They pushed me and beat me and asked me to say what they wanted,” she says. “Speak out against the Mujahedin.”

The MEK is the largest member of the Paris-based National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI), and is directed by Maryam Rajavi. It operates an extensive clandestine network inside Iran and given intelligence to the West on secret facilities for Tehran’s nuclear weapons research, among other activities.